Chapter 3 Positioning, abstract overview and illustrative domain

In this chapter, we position our work with respect to the state of the art, and the identified objectives and challenges. We first describe our methodology, and justify the reasons behind some of our design choices. Then, we present what we call the “ethical model”, which is a systematic framework we use to structure our work. Section 3.3 contains an overview, or conceptual architecture, of the contributions that we detail in the other chapters of this manuscript. Finally, we introduce in Section 3.4 our use-case, a Smart Grid simulator of energy distribution that we will use throughout our experiments. We emphasize that our propositions are agnostic to the application case; this Smart Grid simulator is used as both an evaluation playground, and an exemple to anchor the algorithms in a realistic scenario.

3.1 Methodology

Our methodology is based on the following principles, which we detail below:

- Pluri-disciplinarity

- Incremental approach

- Logical order of contributions

- Human control in a Socio-Technical System

- Diversity and multi-agent

- Co-construction

The first principle of our methodology is its pluri-disciplinar character. Although I was myself only versed in multi-agent systems and reinforcement learning at the beginning of this thesis, my advisors have expertise in various domains of AI, especially multi-agent systems, learning systems, symbolic reasoning, agent-oriented programming, and on the other hand philosophy, especially related to ethics and AI. These disciplines have been mobilized as part of the ETHICS.AI research project.

A second, important principle of our methodology is that we propose an incremental approach, through successive contributions. Thus, we evaluate each of our contributions independently and make sure each step is working before building the next one. In addition, it allows the community to reuse or extend a specific contribution, without having to consider our whole architecture as some sort of monolith. Even though these contributions can be taken separately, they are still meant to be combined in a coherent architecture that responds to the objectives identified in Chapter 1. Thus, it is natural that a specific contribution, taken in isolation, includes few limitations that are in fact focused on in another contribution. At the end of each chapter, we discuss the advantages of the proposed contribution, its limitations and perspectives, and we explicitly note which ones are answered later in the manuscript. We recall that, as mentioned in Chapter 1, this had an impact on this document’s structure, which thus presents models and related experiments in the same chapter.

Contributions have been made, and are presented, in a logical order. As we detail in Section 3.3 and the following chapters, we first describe 2 reinforcement learning algorithms, which focus on learning behaviours aligned with moral values and adaptation to changes. Once we have the learning algorithms, we can detail how to construct reward functions through symbolic judgments, in our second contribution: having proposed the RL algorithms beforehand allows us to evaluate our new reward functions, whereas the RL algorithms themselves can be evaluated on more traditional, mathematical reward functions. Finally, with the new reward functions that contain several explicit moral values through different judging agents, we can now focus on the question of dilemmas and conflicts between moral values.

We recall that we place our work in the larger scope of a Socio-Technical System, and we particularly focus on giving control back to humans. In this sense, the system that we propose must be taught how to behave accordingly to the moral values that are important to us. In other words, it is not that AI “solves” ethics for us humans, but rather humans (designers, but also users) who try to embed mechanisms into AI systems so that their behaviours will become more “ethically-aligned”, and thus will empower humanity. This mindset influenced our propositions, and particularly the second contribution in Chapter 5, where one of the main goals is to make the reward function more understandable, and thus, scrutable by humans. It influenced even more so our third and last contribution in Chapter 6, in which we focus on human preferences, and explicitly give them control through interaction over the artificial agents’ behaviours.

Another important aspect is that we focus on the richness of the use case. This stems from the diversity captured in the environment, which comes from several sources. First, the environment dynamics themselves, and the allowed interactions within the environment, through the designed observations and actions that we detail in Section 3.4, imply a variety of situations. Secondly, diversity is also related to the multiple moral values that agents need to take into consideration. And finally, as highlighted in the state of the art, we propose to increase diversity through the inclusion of multiple learning agents: agents may have different profiles, with different specificities, all of which suggesting different behaviours. We thus adopt the multi-agent principle as part of our method.

This multi-agent aspect starts on a single level in the first contribution, but becomes multi-level due to the addition of judging agents in the second contribution. This supports another important principle of our methodology, although we could not specify this as an objective of this thesis: the co-construction of agents. We did not have time to fully embrace co-construction, which is why it is not defined as an objective; nonetheless, we kept this notion in mind when designing our contributions. By co-construction, we mean that two different agents, which could be both human agents, both artificial, or even a mixed human-artificial combination, learn from each other and improve themselves through interaction with the other. That idea of co-construction is why we present our second contribution as “agentifying” the reward function: by making judging agents instead of simply judging functions, we pave the way for co-construction. Constructive relationships already occur in one of the two directions, as the learning agents improve their behaviour based on the signals sent by judging agents. But, in a larger scope, we could imagine judging agents also learning from learning agents, for example adapting their judgment behaviour so as to help the learners, in some sort of adversarial or active learning, thus enabling construction in the second direction and achieving co-construction. Another possibility of co-construction would be to make humans reflect on their own ethical considerations and preferences, through interaction with learning and judging agents. In this case, learning agents could act as some sort of simulation for example, the human users could try different preferences and discover the impact of their own preferences on the environment. Again, we emphasize that we did not have time to explore all these interesting research avenues. Yet, to keep co-construction attainable in potential future extensions, we tried and designed our contributions with this notion in mind.

3.2 The ethical model

In this section, we take a step back on the technical aspect of producing “ethical systems”, or rather “ethically-aligned systems”, and reflect on how can we achieve this from a philosophical and societal point of view. The ultimate goal is to have a satisfying “ethical outcome” of the system, in terms of both its resulting behaviour, i.e., the actions it proposes or takes, and also how the system functions, i.e., which inputs it takes, what resources the computation requires, etc.

We have mentioned in the previous section that the general framework of this thesis is a Socio-Technical System (STS), in which we want to give the control back to the humans. This focus on STS when talking about AI and ethics has been championed by several researchers. Stahl (2022), notably, describes the discourses on computer ethics, and ethics of AI, and proposes to move towards ethics of digital ecosystems, instead of focusing on specific artefacts. This notion of ecosystems is a metaphor that refers to socio-technical systems in which AI systems and humans interact with each other; as they mention:

Ethical, social, human rights and other issues never arise from a technology per se, however, but result from the use of technologies by humans in societal, organisational and other setting. (Stahl, 2022, p. 72)

In other words, AI systems should not be considered “alone”, but rather as a part of a more complex system incorporating humans. By focusing on STS, they hope to be able to explore and discover ethical issues related to new technologies, including but not limited to AI, and without the need to clearly define what AI is. In a similar vein, although they primarily focus on trustworthiness and legitimacy instead of ethics, Whitworth & De Moor (2003) propose to take into account users’ requirements and concerns, such as privacy, and other ethics-related issues, directly into the design of STS.

To be ethically aligned with our ethical considerations, AI systems need to be guided. This guidance necessarily comes from humans, as ethics is, for now at least, a privilege of humans. The ethical considerations, through this guidance, are “injected” into systems, and we name this an ethical injection. This injection can take multiple forms, depending on the considered AI system, e.g., it can be part of the data, when we talk about supervised learning, or directly implemented as part of an algorithm’s safeguards, or part of a learning signal, etc. This notion of ethical injection builds, among other things, upon the principles of STS, according to which it is important that the system incorporates human concerns.

From this description of the “ethical injection”, we can see that it relates to the already mentioned “Value Alignment Problem”. This problem has been described by many researchers, including moral philosophers and computer scientists, see, e.g., (Gabriel, 2020; Russell, 2021). It mainly refers to 2 important concerns when building an AI system: first, we humans must correctly articulate the objective(s) that we want the system to solve. For example, proxy objectives may be used to simplify the definition of the true objectives, however we risk getting a behaviour that solves only the proxy objectives, and not the true ones. Secondly, the system must solve these objectives while not taking any action that would contradict our values. For example, reducing the emission of greenhouse gaz by killing all of humanity is not an acceptable solution. In our framework, the “ethical injection” is the technical way of incorporating these ethical considerations, both the true objectives and the values that should not be contradicted, into the AI system.

In order to make an AI system more beneficial for us, it should include the moral values that we want the system to be aligned with. Several works have proposed, notably, principles that AI systems should follow in order to be beneficial (Jobin, Ienca, & Vayena, 2019). Another work debates this, and recommends instead focusing on tensions, as all principles cannot be applied at the same time (Whittlestone, Nyrup, Alexandrova, & Cave, 2019). In any way, we argue that, as the vast majority of these choices do not target only technical considerations, they cannot, or should not, be made in isolation by AI experts. They must in fact involve a larger audience, from several disciplines and origins: AI experts, domain experts, philosophers, stakeholders, and impacted or interested citizens.

Yet, this idea raises a problem: these various participants do not have the same knowledge, and therefore need some common ground, so that they can discuss the ethical choices together. This common ground is necessary, we believe, to produce definitions that are both technically doable, and morally suitable. For example, the definition of justice, or fairness, can be difficult to implement by AI experts alone, as multiple definitions are used by different cultures, see for example Boarini, Laslier, & Robin (2009). Which one should they use? On the other hand, definitions produced by non-technical experts may prove difficult, or even impossible, to implement, because they rely on abstract notions.

Discussion between the various participants should yield the ethical injection, that is, the data and design choices used to guide the system towards an ethical outcome. For example, making the explicit choice of using a simplified model, which requires less computational resources (Green IT) would be considered part of the ethical injection. Similarly, the choice of the inputs that the system will be given access to can be considered part of the ethical injection, especially if the choice implies notions of privacy, accuracy, etc. Finally, in a learning system, the choice of the training data will also be important for the ethical injection, as it represents the basis from which the system will derive its behaviour.

Reaching this common ground is not trivial, as participants may come from different domains. Yet, it is crucial, because design choices shape the way the system works, and some of them have ethical consequences. The various ways and loci of ethical injection should thus be discussed collectively: to do so, the AI system needs to be simplified, so that the discussion can focus on the important aspects, without being diverted by details. Still, it should not be too much simplified, otherwise we would risk obtaining a wrong mental model of the system. For example, simplifying too much the idea of a physical machine, e.g., when talking about Cloud-based solutions, would make participants forget about the physical impact of computation, in terms of resources (energy, space, etc.). Simplifying too much about AI systems’ capabilities could raise false hopes, or make them believe that the system is never wrong. Presenting the correct level of simplification, i.e., neither too little nor noo much, is at the crux of getting this common ground.

Figure 3.1 represents an agnostic system in interaction with a human society. The diverse arrows, such as “construct computational structure”, “construct input”, “produce input”, etc., all represent potential loci of ethical injection. On the left side of the figure, humans with various roles, e.g., designers, users, or stakeholders, discuss and interact with the system, on the right side. The “interface” represents the way the system can communicate with the external world, which includes our human society; the interface is composed of inputs and outputs, of which the structure is chosen by the humans. Inputs, in particular may also be produced by humans, e.g., datasets.

Figure 3.1: Representation of a Socio-Technical System, in which multiple humans construct and interact with a system.

In the rest of the manuscript, we consider notably that the moral values, the reward functions, especially when constructed from symbolic judgments, and the contextualized preferences, are the main components of the ethical injection, aside with a few design choices that protect privacy for example. We focus on the technical ability of the learning system to leverage this ethical injection, and thus we place ourselves as the “almighty” designers, without discussing with potential users, nor stakeholders. Nevertheless, we defend that, for a real deployment of such systems, into our human society, these choices should be discussed. Moral values, in particular, should be elicited, to make sure that we have not forgotten one of them. We will sometimes refer to this idea of including users and other stakeholders in the discussion, which requires understanding on their part, and therefore intelligibility on the part of the system.

3.3 Conceptual architecture

In this thesis, we propose a multi-agent system, comprised of multiple agents interacting in a shared environment. This architecture can be seen, on an abstract level, as composed of 3 parts, shown in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: Conceptual architecture of our approach, composed of 3 parts in interaction: the learning part, the judging part, and the handling of dilemmas.

First, the learning part that we present in Chapter 4 introduces learning agents, which are tasked with learning an ethical behaviour, i.e., a behaviour aligned with moral values that are important to humans. To do so, they contain a decision and a learning processes, which feed each other to choose actions based on observations received from the shared environment, and to learn how to choose better actions. The shared environment receives the learners’ actions and computes its next state based on its own dynamics. Observations from the environment state, which include both global data and local data specific to each agent, are then sent to the learning agents so that they can choose their next action, and so on.

The second part concerns the construction of the reward signal, which is sent to the learning agents as an indication of the correctness of their action. Whereas we do not know exactly which action should have been performed (otherwise we would not need to learn behaviours), we can judge the quality of the action. An action will rarely be 100% correct or incorrect; the reward signal should therefore be rich enough to represent the action’s correctness, and accurately reflect the eventual improvement, or conversely deterioration, of the agents’ behaviour. Learning agents will learn to select actions that yield higher rewards, which are better aligned with our moral values, according to the reward function. In order to construct this reward function, we propose in Chapter 5 to use distinct judging agents, each tasked with a specific moral value and the relevant moral rules. Judging agents employ a symbolic reasoning that is easier to design, and more understandable.

Finally, the last part focuses on addressing the specific situations of ethical dilemmas, when multiple moral values are in conflict and cannot be satisfied at the same time. In order to, on the first hand, be able to identify these dilemmas, and on the second hand to manage them, we introduce in Chapter 6 an extension to the learning algorithm. Instead of the simpler configuration in which learning agents receive an aggregated reward, the new learning algorithm receives multiple rewards, one for each moral value. A new process, specialized on dilemmas, is introduced and interacts with human users to identify situations that are relevant to them, and to learn their ethical preferences so as to automatically settle dilemmas accordingly. The goal of the learning agents is thus to learn to settle the dilemmas according to humans’ contextualized preferences; this implies a certain number of interactions between the learning agents and the human users. As the agents learn the users’ preferences, the amount of interactions decreases, thus avoiding putting too much of a burden on the human users.

3.4 Smart Grids as a validation use-case

In order to demonstrate that our proposed approach and contributions can be effectively applied, we developed a Smart Grid simulator.

We emphasize that this simulator is meant only as a validation domain: the approach we describe in this thesis is thought as generic. In particular, the learning algorithms could be leveraged for other domains.

3.4.1 Motivation

The choice of the Smart Grid use-case is motivated by our industrial partner Ubiant, which has expertise in this domain and helped us make a sufficiently realistic (although simplified) simulation. We also argue that this use-case is rich enough to embed ethical stakes, in multiple situations, concerning multiple moral values and multiple stakeholders, as per our objectives and hypotheses.

One may wonder why we chose to propose a new use-case, rather than focusing on existing “moral dilemmas” that have been proposed by the community of researchers: Trolley Dilemmas, Cake or Death, Care robot for alcoholic people, etc. 3 As LaCroix points out, moral dilemmas have been misunderstood and misused in Machine Ethics, especially the trolley-style dilemmas (LaCroix, 2022). For example, the well-known Trolley Dilemma (Foot, 1967; Thomson, 1976) was meant to highlight the difference between “killing” and “letting die”. Whereas it may seem acceptable (or even desirable) to steer the lever, and letting 1 people die to save 5 another, we also intuitively dislike the idea of a person pushing someone (the Fat Man variation), or of a physician killing voluntarily a healthy person to collect their organs and save 5 patients. Although consequences are very similar (1 person dies; 5 are saved), there is a fundamental difference between “killing” and “letting die”, which makes the former unacceptable. This observation was one of the primary goals of the Trolley Dilemma and similar philosophical thought experiments, which have since led to countless discussions and applications in moral philosophy. However, regardless of their importance for the study of philosophical and legal concepts, they do not represent realistic case studies for simulations aimed at learning or implementing ethically-aligned behaviours.

Therefore, instead of focusing solely on “moral dilemmas”, we want to consider an environment with ethical stakes. These ethical stakes transpire at different moments (time steps) of the simulation. Contrary to moral dilemmas, they sometimes may be easy to satisfy. Indeed, we see that in our lives, we are not always in a state of energy scarcity, nor in an impeding-death scenario when we drive. However, even in these scenarii, there are stakes that the artificial agent should consider. Even when it is simple to consume, because there is no shortage, the agent should probably not consume more than it needs, in order to let other people consume as well. Machine Ethics approaches should be validated on these “simple” cases as well. And, on the other hand, there are “difficult” situations, when two (or more) moral values are in conflict and cannot be satisfied at the same time. In this case, which we call a dilemma, although not in the “thought experiment” sense, a compromise must be made.

3.4.2 Definition

As Smart Grids are a vivid research domain, there are several definitions of a Smart Grid, and more generally, Smart Energy Systems. Hadjsaïd & Sabonnadière (2013) note that these definitions depend on the priorities of actors behind the development of these grids, such as the European Union, the United States of America, or China. We propose to focus on the EU’s definition (EU Commission Task Force for Smart Grids, 2010) in order to highlight one of the major differences between smart and “non-smart” grids:

Definition 3.1 (Smart Grid) A Smart Grid is an electricity network that can cost efficiently integrate the behaviour and actions of all users connected to it – generators, consumers and those that do both – in order to ensure economically efficient, sustainable power system with low losses and high levels of quality and security of supply and safety. Though elements of smartness also exist in many parts of existing grids, the difference between a today’s grid and a smart grid of the future is mainly the grid’s capability to handle more complexity than today in an efficient and effective way. A smart grid employs innovative products and services together with intelligent monitoring, control, communication, and self-healing technologies in order to:

- Better facilitate the connection and operation of generators of all sizes and technologies.

- Allow consumers to play a part in optimising the operation of the system.

- Provide consumers with greater information and options for how they use their supply.

- Significantly reduce the environmental impact of the whole electricity supply system.

- Maintain or even improve the existing high levels of system reliability, quality and security of supply.

- Maintain and improve the existing services efficiently.

- Foster market integration towards European integrated market.

As can be seen in definition 3.1, smart grids add various technologies (“innovative products and services”), in order to improve and extend the grid’s functionalities. For example, instead of being mere consumers of energy, the introduction of solar panels allow the grid’s participants to become prosumers, i.e., both producers and consumers. In this case, they gain the ability to truly participate in the grid’s energy dynamics by exchanging energy with the grid, and thus other prosumers, in a two-way manner. We refer the interested reader to X. Yu, Cecati, Dillon, & Simões (2011) and Hadjsaïd & Sabonnadière (2013) for more details on Smart Grids, their definitions, and challenges.

Multiple ethical issues have been identified in Smart Grids (Tally, Rowena, & David, 2019), such as: health, privacy, security, affordability, equity, sustainability. Some of them can be addressed at the grid conception level, e.g., privacy and security by making sound algorithms, health by determining the toxicity of exposition to certain materials, and limiting such exposition if necessary. The remaining ones, although partially addressable by design, can also be addressed at the prosumer behaviour level. For example, prosumers can reduce their consumption when the grid is over-used, in order to let other prosumers, more in need, improve their comfort, and avoiding to buy energy from highly polluting sources.

Specifically, we imagine the following scenario. A micro-grid provides energy to a small neighbourhood of prosumers. Instead of being solely connected to the national grid, the micro-grid embeds its own production, through, e.g., a hydroelectric power plant. Prosumers can produce their own energy through the use of photovoltaic panels, and store a small quantity in their personal battery. They must distribute energy, i.e., choose how much to consume from the micro-grid, from their battery, how much to give back to help a fellow neighbor, how much to buy or sell from the national grid, in order so to satisfy their comfort, supporting a set of moral values all the while. Prosumers are represented by artificial agents that are tasked with taking these decisions to alleviate the prosumers’ life, according to their profiles and wishes. This is another marker of the “smart” aspect in Smart Grids.

3.4.3 Actions

The prosumers take actions that control the energy dynamics within the grid. Prosumers are therefore able to:

- Consume energy from the micro-grid to improve their comfort.

- Store energy in their battery from the micro-grid.

- Consume energy from their battery to improve their comfort.

- Give energy from their battery to the micro-grid.

- Buy energy from the national grid, which is stored in their battery.

- Sell energy from their battery to the national grid.

All of these actions can be done at the same time by a prosumer, e.g., they can both consume from the micro-grid and buy from the national grid. We will detail the exact representation of these actions in Section 4.4. Let us remark that these actions offer the possibility of rich behaviours: prosumers can adopt long-term strategies, e.g., by buying and storing when there is enough energy, in prevision of a production shortage or conversely a consumption peak, and give back when they do not need much.

These actions, and the behaviours that ensue from them, are also often ethically significant. For example, a prosumer who consumes too much energy might prevent another one from consuming enough, resulting in a higher inequality of comforts.

Our goal is therefore to make artificial agents learn how to consume and exchange energy, as some sort of proxy for the human prosumers. These behaviours will need to consider and take into account the ethical stakes.

3.4.4 Observations

In order to help the prosumers take actions, they receive observations about the current state of the environment. Indeed, we do not need to consume the same amount of energy at different times. Or, we may recognize that there is inequality in the grid, and decide to sacrifice a small part of our comfort to help the left-behind prosumers.

These observations may be common, i.e., accessible to all prosumers in the grid, such as the hour, and the current available quantity of energy, or they may be individual, i.e., only the concerned agent has access to the value, such as the personal comfort, and the current quantity of energy in the battery. The distinction between individual and common observations allows to take into account ethical concerns linked with privacy: human users may want to keep part of their individual situation confidential.

The full list of observations that each agent receives is:

Storage: The current quantity of energy in the agent’s personal battery.

Comfort: The comfort of the agent, at the previous time step.

Payoff: The current payoff of the agent, i.e., the sum of profits and costs made from selling and buying energy.

Hour: The current hour of the day.

Available energy: The quantity of energy currently available in the micro-grid.

Equity: A measurement of the equity of comforts between agents, at the previous time step, using the Hoover index.

Energy waste: The quantity of energy that was not consumed and therefore wasted, at the previous time step.

Over-consumption: The quantity of energy that was consumed but not initially available at the previous time step, thus requiring the micro-grid to purchase from the national grid.

Autonomy: The ratio of transactions (energy exchanges) that were not made with the national grid. In other words, the less agents buy and/or sell, the higher the autonomy.

Well-being: The median comfort of all agents, at the previous step.

Exclusion: The proportion of agents which comfort was lower than half the median.

3.4.5 Moral values and ethical stakes

We have explored the literature to identify which moral values are relevant in the context of Smart Grids. Several works have identified moral values that should be considered by political decision-makers when conceiving Smart Grids (de Wildt, Chappin, van de Kaa, Herder, & van de Poel, 2019; Milchram, Van de Kaa, Doorn, & Künneke, 2018). These moral values have been defined with the point of view of political decision-makers, rather than prosumers. For example, the “affordability” value originally said that Smart Grids should be conceived such that prosumers are able to participate without buying too much. In our use-case, we want artificial agents to act as proxy for prosumers, and thus they should follow moral values that take the point of view of prosumers. We therefore adapted these moral values, e.g., for the “affordability”, our version states that prosumers should buy and sell energy in a manner that does not exceed their budget.

We list below the moral values and associated rules that are retained in our simulator:

- MR1 – Security of Supply

- An action that allows a prosumer to improve its comfort is moral.

- MR2 – Affordability

- An action that makes a prosumer pay too much money is immoral.

- MR3 – Inclusiveness

- An action that improves the equity of comforts between all prosumers is moral.

- MR4 – Environmental Sustainability

- An action that prevents transactions (buying or selling energy) with the national grid is moral.

3.4.6 Prosumer profiles

In order to increase the richness of our simulation, we introduce several prosumer profiles. A prosumer agent represents a building: we do not consider a smaller granularity such as buildings’ parts, or electrical appliances. Prosumer profiles determine a few parameters of agents:

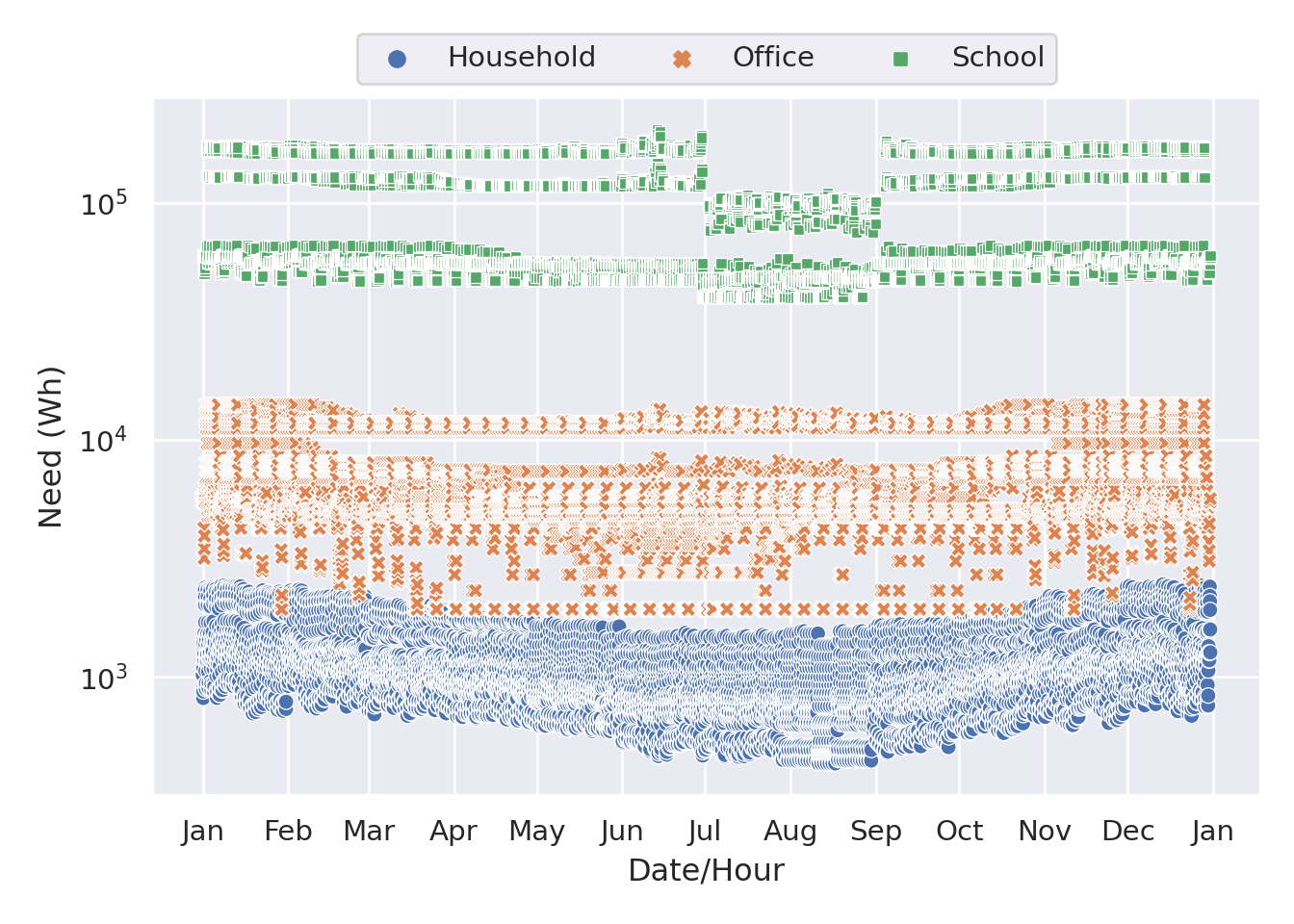

The needs in terms of Watt-hours of the buildings’ inhabitants, for each hour of the year. This need is extracted from public datasets of energy consumption: given the energy consumed by a certain type of building, during a given hour, we assume this represents the amount of energy the inhabitants needed at this hour. The need acts as some sort of target for the artificial agents, which must learn to consume as close as possible to the target need, according to MR1, for every hour of the year. Seasonal changes implies different needs, for example we have a higher consumption in Winter, due to the additional heating.

The personal storage’s capacity. Each building has a personal storage, or battery, that they can use to store a limited quantity of energy. This limit, that we call the capacity, depends on the size of the (typical) building: smaller buildings will have a smaller capacity.

The actions’ maximum range. As we have seen previously, actions are represented by quantities of energy that are exchanged. For example, a household could perform the action of “consuming \(572\)Wh”. Learning algorithms require this range to be bounded, i.e., we do not know how to represent “consume infinite energy”; we chose to use different ranges for different profiles. Indeed, profiles of larger buildings have a higher need of energy. Thus, we should make it possible for them to consume at least as much as they can possibly need. For example, if a building has a maximum need, along all hours of the year, of \(998\)Wh, we say that its action’s maximum range is \(1,000\)Wh.

To define our building profiles, we used an OpenEI public dataset of energy consumption (Ong & Clark, 2014), which contains consumptions for many buildings in different places in the United States of America. We have defined 3 profiles, based on Residential, which we rename Household, Office, and School buildings from the city of Anchorage:

- The Household type of agents has an action range of \(2,500\)Wh, and a personal storage’s capacity of \(500\)Wh.

- The Office type of agents has an action range of \(14,100\)Wh, and a personal storage’s capacity of \(2,500\)Wh.

- The School type of agents has an action range of \(205,000\)Wh, and a personal storage’s capacity of \(10,000\)Wh.

Figure 3.3 shows the need, for each hour in a year, for these 3 profiles.

Figure 3.3: Energy need for each of the building profiles, for every hour of a year, from the OpenEI dataset.

3.4.7 Summary

We summarize this proposed use-case in Figure 3.4. As we can see, the grid contains several buildings, each represented by a learning (prosumer) agent. Three buildings profiles are available: Household, which represents a small, single-family habitation; Office, which represents a medium-sized office; and School, which represents a large building with important needs. Each building has a solar panel that regularly produces energy, and a personal storage in which the energy is stored. They are linked to a Smart Grid, which contains a source of energy shared by all buildings, e.g., a hydraulic power plant, and which is also linked to the national grid. The buildings receive observations from the environment, which can be either individual (local) data that concern only a given agent, or shared (global) data that are the same for all buildings at a given time step. This protects the privacy of the buildings’ inhabitants, as it avoids sharing, e.g., the payoff, or comfort, of an agent to its neighbors. In return, they take actions that describe the energy transfers between them, their battery, the micro-grid power plant, and the national grid.

Figure 3.4: A Smart Grid as per our definition. Multiple buildings (and their inhabitants) are represented by artificial agents that learn how to consume and exchange energy to improve the comfort of the inhabitants. Buildings have different profiles: Household, Office, or School.

References

A list of dilemmas can be found on the now defunct DilemmaZ database, accessible through the Web Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20210323073233/https://imdb.uib.no/dilemmaz/articles/all↩︎